…but it doesn’t have to be.

Hello all. Welcome to the 103rd edition of TEPS Weekly! Yes! We are changing the name of our newsletter to TEPS Weekly. What does that mean for you? Not much has changed - we will be coming to you every week as per usual, but it makes it easier for you to know that all our educator-facing solutions have the same brand - TEPS (Teachers and Educators Professional Skilling).

You may have heard many people say that as students, they hated their History classes and found them very monotonous. However, as adults, many of them enjoy history, watch historical films, and even discuss them. Why is it that as adults, we are engaged and interested in history, but as students, almost everyone around us had bad experiences? The historical facts in museums or historical films remain the same as in school. So, if it is not about the content, it most likely is the pedagogy—the way it is delivered.

What does a typical History class look like?

Mr. Arora is a Middle School History teacher in Ludhiana. He begins teaching the chapter Nationalism in India by asking students to open their textbooks. He reads through the chapter and pauses occasionally to explain key events, figures and concepts. With just 10 minutes of the lesson left, he asks students to note down important dates and facts. Then, he tells them to complete an exercise at the end of the chapter and also where they can find the answers. In the corner of the classroom, one student doodles while another student thinks, “What is the point of this?”

Why do students disengage in Mr. Arora’s class?

Rote Memorisation Over Understanding

A common problem in teaching and learning history is that students are expected only to rote-learn facts and recall them for examinations. This limits students’ understanding by reducing history to memorisation of dates and events.

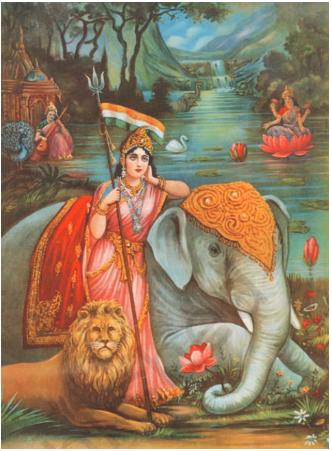

In Mr. Arora’s classroom, the lesson focuses mainly on memorising events rather than understanding their significance. For example, students are expected to remember what the value of art is in nationalism but not to understand the art itself and how it unifies people or excludes some.

Passive Learning

The pedagogical approach here focuses on repeating what the textbook says and writing answers. In situations like these, students are not active learners.

Mr. Arora gives students time to talk, but only to read aloud from the textbook. He does not take any steps to involve them more in the lesson. A History class should not just be about remembering and recalling facts. It should give students the opportunity to question, investigate, interpret, and communicate. For example,asking students how the Non-Cooperation Movement was different in the countryside, towns and plantations and analysing the reasons for it being different.

Lack of Relevance

Many students do not find history relevant or useful. Memorising so many facts, timelines and dates often feels boring and dull. If students do not feel connected to what they are learning, they quickly lose interest.

A topic like Nationalism in India affects students every day. If Mr Arora just goes through the textbook, there is no guarantee that students will understand how Nationalism affects their lives; for example, some holidays like the Independence Day and Republic Day have roots in Nationalism. Nationalism of late is also the theme of the most celebrated movies of Indian cinema like RRR or Rang de Basanti.

Bringing out relevance also helps students connect the events of Indian Nationalism to those of the rest of the world—something they have already learned about.

How can Mr. Arora make his class more engaging?

By Encouraging Deeper Thinking

History is a content-heavy subject, so the teacher has to talk a lot. The trick is to make it interesting by varying how we present content and use questions to encourage students to think deeply and beyond the textbook.

Recall: These questions ask students about key details from the textbook.Which satyagraha did Mahatma Gandhi organise first?

Comprehension: These questions assess students’ understanding of the information.Which actions of Mahatma Gandhi show that he firmly believed in non-violence?

Analysis: These questions require students to infer, interpret and compare information, consider the author’s perspective or connect ideas to prior knowledge.What was common between the French Revolution and Nationalism in India?

Extrapolation: These questions ask students to compare, contradict, or support their answers with evidence.Think about the features of the Civil Disobedience Movement and the Non-Cooperation Movement and plan a new Movement that Mahatma Gandhi could have launched in the 1940s.

Invention: These questions require students to imagine. They may start with “If you could…” or “What if…?”If you were a farmer, how would you have supported the Non-Cooperation Movement?

Evaluation: These questions ask students to evaluate events, actions, or sources.Was the rejection of the Simon Commission justified?

By Ensuring Active Learning through Writing

Writing assignments and tests in history often have a bad reputation. Teachers find them tedious to assess, and students dislike writing them. However, writing is one of the key ways to assess historical understanding. To make history writing more engaging, we can design assignments that encourage students to classify, organise or argue their ideas.

Descriptive Writing: Descriptive writing in history involves explaining events, causes and consequences in detail, based on factual information.. Here is an example from NCERT :

Expressive Writing: This form of writing allows students to engage with historical events at an emotional and intellectual level by taking on perspectives, expressing opinions and making persuasive arguments. Assignments may include role-play, debates, speeches or creative writings. Two examples are:Imagine you are a freedom fighter in India during the Quit India Movement. Write a speech to inspire others to join the cause.

Participate in a role-play as a leader of the Swadeshi Movement. Write a speech convincing people to boycott British goods and support Indian industries.

Imaginative Writing: This form of writing encourages creativity by asking students to place themselves in historical situations and respond as if they were part of that time. However, these responses must still be based on historical facts and perspectives. Questions may start with 'What if…?' or 'If you could…?' to encourage critical thinking within a historical context. An example from NCERT is:

Analytical Writing: This form of writing requires students to deeply read information, interpret sources and draw logical conclusions. This may include identifying patterns in historical events, comparing perspectives, assessing cause-and-effect relationships or analysing historical images and texts. An example from NCERT is:

Evaluative Writing: This form of writing requires students to assess historical events or figures by weighing different perspectives, comparing significance and determining impact. Students must justify their arguments with historical examples and evidence. Some examples are:

Does nationalism always lead to positive outcomes? Evaluate using examples from India’s independence movement.

Which Nationalist Movement was the most inclusive? Evaluate using examples from India’s independence movement.

By Making History Relevant

So much of what is happening around the world today can be understood better by understanding history. For example, the Ukraine-Russia war can be understood by Russia annexing Crimea in 2014, the USSR breaking up in 1991 and so on. For students to be invested in history, they need to understand that past events still matter. To do this, we can:

Start Strong by Hooking Interest

History is taught chronologically. In that sense, a lot of times the most exciting or moving parts come much later. Starting strong means introducing students to something eventful we cover in our lessons. This keeps them hooked till the end… till the engaging part. Starting strong makes history seem real or imaginable. A hook like this is bound to make students more curious, and hopefully, act like ‘investigators’ and ask, “Why did this happen?” For example, to cover the ‘Civil Disobedience Movement’ we can say,

“Thousands marched behind Gandhi, breaking a law by making salt. The British arrested them, but the movement grew stronger. Why did this simple act shake an empire? Let us find out.”

Connect History to Students’ Present

Encourage students to relate historical events to their own experiences or things they already know. Teaching history can not be just about knowing what happened in the past, it is also how past events affect us today. For example:

Activity: Bring in a news article about the vandalism of Mahatma Gandhi’s statue in Melbourne (2021), which sparked debates about his legacy. Discuss how historical figures and events continue to shape political and social issues today through questions like:

Which values of Gandhi make him a celebrated public figure today?

How did Gandhi contribute to Nationalism in India?

Why did vandalising Gandhi’s statue hurt people?

Why is Gandhi celebrated as the ‘Father of the Nation’?

Question: Does your family have any stories about India’s independence or partition?

A great way to teach history is through analogies. While talking about something in the past, connect it to something similar that students might be aware of. For example, the Bengal Famine could be compared to COVID-19 in terms of impact.

Similarly, making longitudinal connections is important. Longitudinal connections mean how something in the present is somehow and somewhat caused by events in history. It helps students understand the importance of what they are learning. For example, the Partition of India in 1947 not only shaped the political boundaries of South Asia but also influenced present-day India-Pakistan relations. Even today, diplomatic relations between the two countries are shaped by the historical events of the freedom struggle and Partition.

Use First-Person Narratives

First-person narratives help students empathise with historical figures and actions. We can also use these narratives as discussion starters. When a student learns about the Jallianwala Bagh incident from the textbook, supplementing it with a diary entry/ journal from someone whose family was impacted by the incident does not just make the students understand the incident at a personal level, it also helps students see history not just as a series of events but as a people’s story and experiences. First-person narratives help students weave multiple events together as they may explain causes for behaviour/ actions. An example from NCERT is:

To conclude, history is more than just a series of events that happened. We can make understanding history interesting and engaging by asking students to think deeply, by giving them writing assignments that go way beyond memorisation and most importantly, connecting history to our students’ lives to make them experience it. If at all someone says history is only about the past, ask them why an India-Pakistan cricket match is so popular.

If you found this newsletter useful, please share it.

If you received this newsletter from someone and you would like to subscribe to us, please click here.

Edition: 4.10